The excellent Autonomies website has begun posting a translation of Tomás Ibáñez’s 2014 essay, “Anarchism is movement: Anarchism, neoanarchism and postanarchism.” Here I present excerpts from the conclusion to Ibáñez’s introduction. Ibáñez grew up in France, where his parents found refuge following the crushing of the Spanish anarchist movement at the end of the Spanish Civil War. As a youth, he become active in the Spanish anarchist exile group, Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias (FIJL). Autonomies notes that in “1968, he joined the March 22 Movement, participating actively in the May events of that year, until his arrest in June, and subsequent forced ‘internal exile’ outside Paris. In 1973 he returned to Spain and participated in the attempts to rebuild the CNT.” While I don’t agree with Ibáñez on some points, he is a thoughtful and provocative contemporary anarchist writer well worth reading (one area of disagreement is that I see anarchy as something that preceded the creation of explicitly anarchist doctrines, and believe that anarchist ideas can not only continue to exist without a movement, and in fact preceded the creation of any anarchist movements, but in those historical interregnums between the efflorescence of anarchist movements when the burden of anarchism’s historical past is less pressing, as are pressures for ideological uniformity precisely because of the seeming political irrelevance of anarchists (but not anarchism), anarchists can and have revitalized anarchist thinking about contemporary events, and future prospects, helping lay the groundwork for yet another resurgence of anarchist activity. This was particularly true in Europe and North and Latin America in the 1940s and 50s, as I have argued in my essay, “The Anarchist Current”).

From May 1968 to the 21st Century

After having demonstrated an appreciable vitality for about a century – grosso modo between 1860 and 1940, that is, some 80 years -, anarchism fell back, inflected back upon itself and practically disappeared from the world political stage and from social struggles for various decades, undertaking a long journey in the wilderness that some took advantage of to extend their certificate of dysfunctionality and to speak of it as of an obsolescent ideology which only belongs to the past.

The fact is that, after the tragic defeat of the Spanish Revolution in 1939, if an exception is made for the libertarian presence in the anti-franquista struggle, of the participation of anarchists in the anti-fascist resistance in certain regions of Italy during WWII or the active participation of British anarchists in the anti-nuclear campaigns of the end of the 1950s and the early 1960s or, also, a certain presence in Sweden and Argentina, for example, anarchism remained strikingly absent from the social struggles that marked the next thirty years in the many countries of the world, limiting itself in the best of cases to a residual and testimonial role. Marginalised from struggles, unable to renew ties with social reality and relocate itself in political conflict, anarchism lost all possibility of re-actualising itself and of evolving.

In these unfavourable conditions, anarchism tended to fold in upon itself, becoming dogmatic, mummified, ruminating on its glorious past and developing powerful reflexes of self-preservation. The predominance of the cult of memory over the will to renew led it, little by little, to make itself conservative, to defend jealously its patrimony and to close itself in a sterilising circle of mere repetition.

It is a little as if anarchism, in the absence of being practiced in the struggles against domination, had transformed itself slowly into the political equivalent of a dead language. That is, a language that, for lack of use by people, severs itself from the complex and changing reality in which it moved, becoming thereby sterile, incapable of evolving, of enriching itself, of being useful to apprehend a moving reality and affect it. A language which is not used is just a relic instead of being an instrument; it is a fossil instead of being a living body, and it is a fixed image instead of being a moving picture. As if it had been transformed into a dead language, anarchism fossilised itself from the beginnings of the 1940s until almost the end of the 1960s. This suspension of its vital functions occurred for a reason that I will not cease to insist upon and this is none other than the following: anarchism is constantly forged in the practices of struggle against domination; outside of them, it withers away and decays.

Stuck in the trance of not being able to evolve, anarchism ceased to be properly anarchist and went on to became something else. There is no hidden mystery here, it is not a matter of alchemy, nor of the transmutation of bodies, but simply that if, as I maintain, what is proper to anarchism is rooted in being constitutively changeable, then the absence of change means simply that one is no longer dealing with anarchism…

One has to wait until the end of the 1960s, with the large movements of opposition to the war in Vietnam, with the incessant agitation on various campuses of the United States, of Germany, of Italy or of France, with the development, among a part of the youth, of nonconformist attitudes, sentiments of rebellion against authority and the challenge to social conventions and, finally, with the fabulous explosion of May 68 in France, until a new stage in the flourishing of anarchism could begin to sprout.

Of course, even though strong libertarian tonalities resonated within it, May 68 was not anarchist. Yet it nevertheless inaugurated a new political radicality that harmonised with the stubborn obsession of anarchism to not reduce to the sole sphere of the economy and the relations of production the struggle against the apparatuses of domination, against the practices of exclusion or against the effects of stigmatisation and discrimination.

What May 68 also inaugurated – even though it did not reach its full development until after the struggles in Seattle of 1999 – was a form of anarchism that I call “anarchism outside its own walls” [anarquismo extramuros], because it develops unquestionably anarchist practices and values from outside specifically anarchist movements and at the margin of any explicit reference to anarchism.

May 68 announced, finally, in the very heart of militant anarchism novel conceptions that, as Todd May says – one of the fathers of postanarchism, whom we will speak of below -, privileged, among other things, tactical perspectives before strategic orientations, outlining thereby a new libertarian ethos. In effect, actions undertaken with the aim of developing political organisations and projects that had as an objective and as a horizon the global transformation of society gave way to actions destined at subverting, in the immediate, concrete and limited aspects of instituted society.

Some thirty years after May 68, the large demonstrations for a different kind of globalisation [altermundista] of the early 2000s allowed anarchism to experience a new growth and acquire, thanks to a strong presence in struggles and in the streets, a spectacular projection. It is true that the use of the Internet allows for the rapid communication of anarchist protests of all kinds that take place in the most diverse parts of the world; and it is obvious that it permits assuring an immediate and almost exhaustive coverage of these events; but it is also no less certain that no single day goes by without different anarchist portals announcing one or, even, various libertarian events. Without letting ourselves be dazzled by the multiplying effect that the Internet produces, it has to be acknowledged that the proliferation of libertarian activities in the beginning of this century was hard to imagine just a few years ago.

This upsurge of anarchism not only showed itself in struggles and in the streets, but extended also to the sphere of culture and, even, to the domain of the university as is testified to by, for example, the creation in October of 2005, in the English university of Loughborough, of a dense academic network of reflection and exchange called the Anarchist Studies Network, followed by the creation in 2009 of the North American Anarchist Studies; or as is made evident by the constitution of an ample international network that brings together an impressive number of university researchers who define themselves as anarchists or who are interested in anarchism. The colloquia dedicated to different aspects of anarchism – historical, political, philosophical – do not cease to multiply (Paris, Lyon, Rio de Janeiro, Mexico and a vast etcetera).

This abundant presence of anarchism in the world of the university cannot but astound us, those who had the experience of its absolute non-existence within academic institutions, during the long winter that Marxist hegemony represented, that followed conservative hegemony, or that coexisted with it, above all in countries like France and Italy. In truth, the panorama outlined would have been unimaginable even a few years ago, even at a time as close as the end of the 1990s.

Let us point out, finally, that between May 68 and the protests of the years 2000, anarchism demonstrated an upsurge of vitality on various occasions, above all in Spain. In the years 1976-1978, the extraordinary libertarian effervescence that followed the death of Franco left us completely stupefied, all the more stupefied the more closely we were tied to the fragile reality of Spanish anarchism in the last years of franquismo. An effervescence that was capable of gathering in 1977 some one hundred thousand participants during a meeting of the CNT in Barcelona and that allowed during that same year to bring together thousands of anarchists that came from all countries to participate in the Jornadas Libertarias in this same city. A vitality that showed itself also in Venice, in September of 1984, where thousands of anarchists gathered, coming from everywhere, without forgetting the large international encounter celebrated in Barcelona in September-October of 1993.

Many were the events around which anarchists gathered in numbers unimaginable before the explosion of the events of May 68. In fact, the resurgence of anarchism has not ceased to make us jump, so to speak, from surprise to surprise. May 68 was a surprise for everyone, including of course for the few anarchists who we were, wandering the streets of Paris, a little before. Spain immediately after Franco was another surprise, above all for the few anarchists who nevertheless continued to struggle during the last years of the dictatorship. The anarchist effervescence of the years 2000 is, finally, a third surprise that has nothing to envy in those that preceded it.

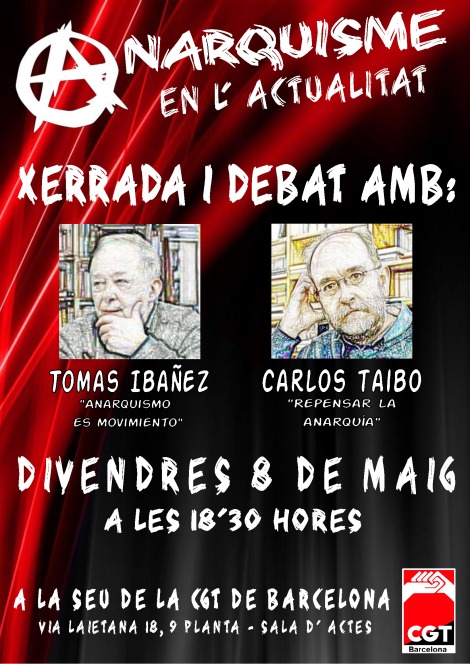

Tomás Ibáñez