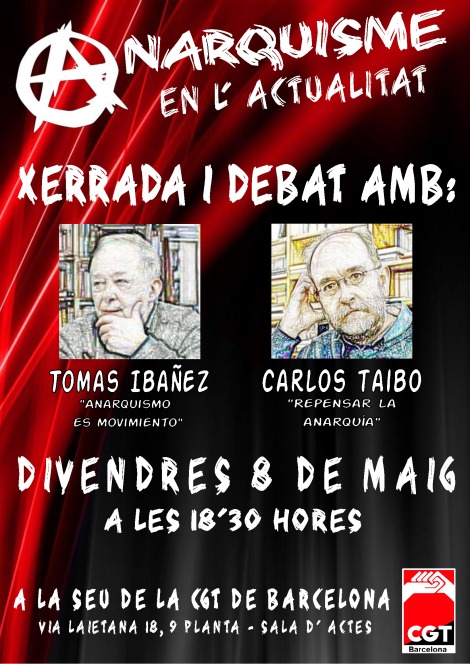

The Autonomies website has recently posted a translation of an essay by the Spanish anarchist, Tomás Ibáñez, “The Anarchism to Come,” which could also be translated as “The Coming Anarchism,” an allusion to Kropotkin’s 1887 article, “The Coming Anarchy.” I thought it fitting to reprint excerpts from Tomás Ibáñez’s essay some 130 years later. While highlighting the necessary differences between contemporary anarchism, historical anarchism, and the “coming anarchism,” Tomás Ibáñez nevertheless argues that there are certain “invariant” elements of classical anarchism that must be preserved in order for something to be considered any kind of anarchism. Originally published in Libre Pensamiento, No. 88.

Current forms of anarchism

I believe that it becomes quite clear that the context in which the coming anarchism will find itself will be eminently different from the context in which it has operated until recently, which can only but substantially modify it.

Some of these changes are already beginning to gain form, such that, to glimpse, even if confusedly, the characteristics of the coming anarchism, it is very useful to observe the current anarchist movement, and especially its most youthful component. This component represents a part of contemporary anarchism that already manifests some differences with classical anarchism, and with that which I have sometimes called “neo-anarchism”.

What we can observe at the present is that, after a very long period of very scarce international presence by anarchism, what is emerging and is already proliferating in very appealing ways in all of the regions of the world, are various collectives concerned with a great diversity of themes; multiple, fragmented, fluctuating and at times ephemeral, but which participate in all of the movements against the system, and sometimes even initiate them. Undoubtedly, this fragmentation corresponds to some of the characteristics of the new context which we are entering and which is making possible a new organisation of the spaces of dissidence. The current reality which is becoming literally “shifting” and “liquid” demands, certainly, much more flexible, more fluid organisational models, oriented according to simple proposals of coordination to realise concrete and specific tasks.

Like the networks that rise up autonomously, that self-organise themselves, that make and unmake themselves according to the exigencies of the moment, and where temporary alliances are established between collectives, these probably constitute the organisational form, reticular and viral, that will prevail in the future, and whose fluidity is already proving its effectiveness in the present.

What seems to predominate in these youthful anarchist collectives is the desire to create spaces where relations are exempt from the coercion and the values that emanate from the reigning system. Without waiting for a hypothetical revolutionary change, it is for them a matter of living from now on as closely as possible to the values that this change should promote. This leads, among the very many other kinds of behaviour, to developing scrupulously non-sexist relations stripped of any patriarchal character, including in the language, or to establishing relations of solidarity that completely escape hierarchical logic and a commodity spirit.

It also contributes, and this is very important, to the weight that is given to those practices that exceed the order of mere discursivity. The importance of doing and, more precisely, of “doing together“, is emphasised, putting the accent on the concrete effects of this doing and on the transformations that it promotes.

In these spaces, the concerts, the fiestas, the collective meals (vegan, of course), form part of the political activity, equal to the putting up of posters, neighbourhood actions, talks and debates, or demonstrations, at times quite forceful. In reality, it is a matter of making the form of life be in itself an instrument of struggle that defies the system, that contradicts its principles, that dissolves its arguments, and that permits the development of transforming community experiences. It is for this reason that, from the new libertarian space that is being woven in different parts of the world, experiences of self-management, of economies of solidarity, of networks of mutual aid, of alternative networks of food production and distribution, of exchange and distribution are developing. The success on this point is complete, for if capitalism is converting itself into a form of life, it is obvious that it is precisely on this terrain, that of forms of life, where part of the struggle to dismantle it must situate itself.

A broad subversive fabric is gaining shape that provides people with antagonistic alternatives to the system, and which, at the same time, helps to change the subjectivity of those who participate in them. This last aspect is terribly important for there exists a very clear awareness, in having been formatted by and for this society, that we have no other remedy than to transform ourselves if we want to escape its control. Which means that desubjectification is perceived as an essential task for subversive action itself.

Lastly, it is by no means infrequent that the alternative anarchist space converges with broader movements, such as those that mobilise against wars, or against summit meetings, and those that from time to time occupy squares rediscovering anarchist principles like horizontalism, direct action, or the suspicion before any exercise of power. In fact, one could consider that these broader movements, which do not define themselves, far from it, as anarchist, represent what at one moment I qualified as outside the walls anarchism, and they prefigure the coming anarchism.

Together with these youthful anarchist collectives, another subversive phenomenon that responds to the technological characteristics of the current moment and which enriches as much the revolutionary practices, as the corresponding imaginary, consists of the appearance of hackers, with the practices and form of political intervention that characterise them.

In a recent book, it is correctly pointed out that if what fascinates and what attracts our attention are macro-concentrations (the occupation of squares, the anti-summit protests, etc.), it is nevertheless in other places where the new subversive politics is being invented: this is the work of dispersed individuals who nevertheless form virtual collectives: the hackers.

In analysing their practices, the author specifies that the value of their struggle resides in the fact that it attacks a fundamental principle of the current exercise of power: the secrecy of State operations, a strictly reserved hunting area and totally opaque to non-authorised eyes, which the State keeps exclusively to itself. The activists draw on a practice of anonymity and of the elimination of traces that does not respond to the demands of secrecy, but to a new conception of political action: the opposite of creating an “us” heroically and sacrificially confronting power in an unmasked and physical struggle. It is about, in effect, not exposing oneself, of reducing the cost of the struggle, but above all of not establishing a relationship, not even of conflict, with the enemy.

The anarchist invariant

Next to its inevitable differences with classical anarchism, a second consideration that we can advance, also in full confidence, is that to continue to be anarchism instead of becoming something else, the new anarchism should preserve some of the constitutive elements of the instituted anarchism. It is these elements that I like to call “the anarchist invariant“, an invariant that unites the current and future anarchism, and that will continue to define, therefore, the anarchism to come.

In fact, this invariant is composed of a small handful of values among which figures prominently that of equaliberty, that is, freedom and equality in common movement, forming a unique and inextricable concept that unites, indissolubly, collective freedom and individual freedom, while at the same time completely excluding the possibility that, from an anarchist perspective, it is possible to think freedom without equality, or equality without freedom. Neither freedom, nor equality, severed from their other half, fall within an approach that continues to be anarchist.

It is this compromise with equaliberty that places within the heart of the anarchist invariant its radical incompatibility with domination in all of its forms, as well as the affirmation that it is possible and, further, intensely desirable, to live without domination. And it is with this that the motto “Neither to rule, nor to obey” forms part of what cannot change in anarchism without it ceasing to be anarchism.

Likewise, anarchism is also denatured if it is deprived of the set formed by the union between utopia and the desire for revolution, that is, by the union between the imagination of a world always distinct from the existing one, and the desire to put to an end this last.

Another of the elements that is inscribed permanently in anarchism is an ethical commitment, especially to the ethical exigency of a consonance between theory and practice, as well as to the demand for an ethical alignment between means and ends. This signifies that it is not possible to attain objectives in accordance with anarchist values along paths which contradict them. Whereby, the actions developed and the forms of organisation adopted should reflect, already, in their very characteristics, the goals sought; they should prefigure them, and this prefiguring constitutes an authentic touchstone for verifying the validity of means. In other words, anarchism is only compatible with prefigurative politics, and it would cease to be anarchism if it abandoned this imperative.

Lastly, neither can one continue to speak properly of anarchism if this renounces the fusion between life and politics. We should not forget that anarchism is simultaneously, and in an indissociable way, a political formulation, but also a way of life, but also an ethics, but also a set of practices, but also a way of being and of behaving, but also a utopia. This implies an interweaving between the political and the existential, between the theoretical and the practical, between the ethical and the political, that is, ultimately, a fusion between the sphere of life and the sphere of the political.

To continue to be “anarchism”, the “coming anarchism” cannot do without any of these elements.

Tomás Ibáñez

Leave a comment