The misrepresentation of the history of the Spanish anarchists, particularly with respect to the Spanish Revolution and Civil War, is something that anarchists have had to combat when the events were occuring and ever since. In this manifesto, Antonio Gascón and Agustín Guillamón challenge continuing attempts to blame on the anarchists every atrocity committed outside of the fascist controlled areas (see also “Autopsy of a Hoax,” regarding the shabby attempts to blame the anarchists for mass executions in Madrid). These misattributions of responsibility go back to the Civil War itself, something that, as the authors point out, George Orwell tried to bring to the world’s attention in his memoir of the Civil War, Homage to Catalonia, which professional historians hostile to anarchism continue to denigrate. Gascón and Guillamón’s manifesto has been translated by Paul Sharkey and was originally posted at Christie Books and then reposted by the Kate Sharpley Library. I included a chapter on the Spanish Revolution in Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas.

The Rag-Pickers’ Puigcerdá Manifesto: Fight for History

The fight put up by workers in order to learn their own history is but one of the many class wars in progress. It is not sheer theory, abstraction nor banality, in that it is part and parcel of class consciousness per se and can be described as theorization of the historical experiences of the world proletariat and in Spain it has to embrace, assimilate and inevitably lay claim to the experiences of the anarcho-syndicalist movement in the 1930s.

There is spectre hanging over historical science, the spectre of falsification. The amnesia worked out between the democratic opposition’s trade unions and political parties with the last management line-up of the Francoist state at the time of the dictator’s demise, was yet another defeat for the workers’ movement during the Transition and it had important implications for how the Francoist Dictatorship and the Civil War are remembered historically. An amnesty amounted to a clean slate and a fresh start with the past. This required a deliberate and “necessary” forgetting of all pre-1978 history. There was a brand new Official History to be rewritten, since the Francoist and the anti-Francoist versions of the past were of no further use to the new establishment, its gaze focused upon papering over the antagonisms that triggered the Spanish Civil War.

At present (April 2018), every reference to conflict or antagonism having been banished from the collective memory along with anything that might make it plain that the Civil War was also a class war, the business of recycling it as a chapter in bourgeois history has peaked. Having played down, covered up or ignored the proletarian and revolutionary character of the Civil War, the mandarins of Official History are busily recuperating the past as the narrative of the formation and historical consolidation of representative democracy, or, in the historically autonomous regions, enshrining the basis of their nationhood.

The working class has had its historical protagonism wrested away from it, to the advantage of the brand-new democratic and nationalistic myths of a bourgeoisie that holds economic and political power. LET US PLACE IT ON RECORD THAT HISTORICAL MEMORY IS A CLASS WAR BATTLEGROUND.

The bourgeois institutions of the state’s cultural apparatus have always controlled and exploited history for their own advantage, by covering up, ignoring or misrepresenting facts that call into question or challenge class rule and, with a few honorable exceptions, the vast majority of academic and professional historians have gone along with this willingly.

As the research presently stands, the book by Pous and Sabaté about Antonio Martín and the Civil War in the Cerdanya, as well as the tiresome repetition of their theses and contentions by virtually every other historian who had dealt with the subject, stands out as the most striking and extreme sample shedding light on the Official History mentioned in this Manifesto. OFFICIAL HISTORY IS THE CLASS HISTORY OF THE BOURGEOISIE.

As a platonic ideal, objectivity is actually non-existent in a society divided into social classes. In the specific instance of the Civil War, Official History is characterized by its EXTRAORDINARY ineptitude and its no less EXTRAVAGANT attitude. The ineptitude resides in its utter inability to achieve, or indeed to strive for, a modicum of scientific rigour. The ATTITUDE springs from its knowing IGNORING or DENIAL of the existence of a hugely mighty revolutionary movement (libertarian, for the most part) which, like it or not, shaped every aspect of the Civil War. These servitors of the bourgeoisie in the field of History are prone to a number of intellectual aberrations (aberrant even from a bourgeois viewpoint):

THEY PRAISE and EULOGIZE the methods and repressive efficacy of the Assault Guards and Civil Guard (renamed the Republican National Guard) or political police (the Military Intelligence Service, or SIM). Perhaps they not very aware that in so doing they are singing the praises of torture. But that is a feature that, like no other, flags up the influence of class outlook and interests in the field of history, because such praise for the efficacy of torture and republican police and judicial crackdowns on revolutionaries, runs parallel to the displays of horror at the class violence unleashed against bourgeois in July 1936 by “uncontrollables”. Experts on the subject of violence and efficient in keeping the books on violent deaths they may well be, but they display total partisanship when they describe as anarchist “terror” or police “efficiency” what was at every step the violence of one class against another. Except that, as far as they are concerned, workers’ violence amounts to terror, whereas, violence coming from the state, the SIM, the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC), the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and Estat Catala is to be classed as “efficiency”. On no grounds other than their class outlook. Violence is judged by double standards, depending on one’s view of the person inflicting or enduring it.

They DENY, though they would rather IGNORE (in that the latter would be handier, more effective and more elegant) the decisive strength with the republican zone of a mostly anarchist revolutionary movement.

They DENY, or so extensively downplay as to misrepresent the documented record of the facts, the hugely repressive, reactionary complicity of the Catholic Church in the army coup d’etat and its active involvement in preparing, unleashing and blessing the subsequent fascist repression.

They DEPLORE George Orwell’s having written an “accursed” book that should never have been read and Ken Loach’s having filmed a “ghastly” movie that ought never to have been watched. We wish to sound the ALARM against a rising tide of revisionist historians of the Civil War.

ALARM at the determined brazen misrepresentation of historical events, in defiance of the available documentary record. The facts themselves are being forced underground and the documentation is ignored or misinterpreted. The writing of Civil War history has shifted from being an activist history written by the protagonists and eye-witnesses to the civil war, (with all of the risks that that implied, but also offering the irreplaceable passion of those who do not dice with words because they had previously diced with death) into a cack-handed, obsolete academic history characterized by bloopers, lack of understanding and even contempt for the militants and organizations of the workers’ movement.

ALARM at the increasing banality of Official History and the methodical marginalization of research that highlights the crucial historical role of the workers’ movement, no mater how rigorous it might be. In actual fact, the bourgeois historians are utterly incapable not just of understanding but even of accepting the historical existence of a mass revolutionary movement in 1936 Spain. We are dealing here with a history that refuses to acknowledge the revolutionary upheaval that played out during the Civil War period.

Official History approaches the Civil War as a fascism-antifascism dichotomy, which facilitates consensus between left- and right-wing academic historians, Catalan nationalists and the neo-stalinists who, across the board, are all agreed in chalking the republic’s failure up to the radicalism of the anarchists, POUMists and revolutionary masses who are thereby made into their shared scape-goats.

By ignoring, omitting or down-playing the proletarian and revolutionary aspects of the period of the Republic and the Civil War, Official History manages to turn the world upside down, so that its leading pontiffs have awarded themselves the task of rewriting the whole thing ALL OVER AGAIN, thereby completing their hijacking of historical memory, in yet another step in the overall process of expropriating the working class. When all is said and done, it is the academic historians who write History. Even as the generation that lived through the war is dying out, the books and handbooks of Official History are ignoring the existence of a magnificent revolutionary anarchist movement and, ten years from now, might dare claim that NO SUCH MOVEMENT EXISTED. The mandarins firmly believe that NOTHING THEY do not write about ever existed: if the history calls the present into question, they deny it.

It is the function of revolutionary history to show that legends, books and handbooks tell lies, misrepresent, manipulate and kowtow to the bureaucratic and class-biased academic discipline.

Faced with the growing bringing of the profession of historian into disrepute, and in spite of whatever honorable and outstanding examples there may be around, we, Antonio Gascón and Agustín Guillamón, abjure the description ‘historian’ in the aim of averting undesirable and unpleasant confusion: grounds enough for us lay claim to the honest pursuit of collectors of ancient testimonies and papers: rag-pickers of history.

Following the political (though not military) defeat of the anarchists in May 1937, in Barcelona and all across Catalonia, the crackdown on the libertarian movement during the summer of 1937 was accompanied by a campaign of insult, degradation, outright lies, abuse and criminalization which conjured up a brand-new reality in place of the social and historical facts: the anti-libertarian black legend which has, since then, become the only acceptable explanation, the only living history. For the first time in history, a political propaganda campaign replaced what had happened by a non-existent, artificially constructed fiction. George Orwell, eye-witness to and a victim of this campaign of denigration, falsehood and demonization, posited a Big Brother in his novels. The academic historians were able to rewrite the past time and again, depending on the shifting sectarian and political interests, the wrath of the gods they worshipped or the tastes and whimsies of whoever was their master. As Orwell wrote in his novel 1984: “Whoever controls the past controls the future. Whoever controls the present controls the past.”

In the realm of historiography, the bourgeoisie’s Hallowed History inherited, pursued and completed this defamatory Stalinist and republican campaign, which needs to be denounced, criticized and demolished. History is but one more fight in the class war in progress. The bourgeoisie’s history we counter with the revolutionary history of the proletariat. Lies are defeated by truth; myths and dark legends by archives.

There is a stark contradiction between the trade of retrieving historical memory and the profession of lackeys of Official History as the latter needs to forget and eradicate the past existence and, consequently, the feasibility in the future, of a redoubtable revolutionary mass workers’ movement. This contrast between trade and profession is resolved by means of ignoring what they know or ought to know; and this makes them redundant. Official History purports to be objective, impartial and all-encompassing. But it is characterized by its inability to acknowledge the class element in its alleged objectivity. It is, of necessity, partisan and cannot embrace any outlook other than the bourgeoisie’s class outlook. And it is, of necessity, exclusivist and banishes the working class from the past, future and present. Official Sociology would have us believe that the working class, the proletariat and the class struggle are no more; and it is up to Official History to persuade us that they never existed.

A perpetual, complacent and a-critical present renders the past banal and eats away at historical awareness.

The bourgeoisie’s historians have to rewrite the past, just the way Big Brother did, time and again. They need to deny that the Civil War was a class war. Whoever controls the present controls the past and whoever controls the past determines the future. Official History is the bourgeoisie’s history and its mission these days is to weave a myth around nationalisms, democracy and market economics, so as to persuade us that these things are eternal, immutable and immoveable.

The promoters of this Manifesto, Antonio Gascón and Agustín Guillamón, having set themselves up as a History Defence Committee, hereby declare themselves belligerents in this FIGHT FOR HISTORY. For that reason, and as set out in our book Nacionalistas contra anarquistas en la Cerdaña (Nationalists versus anarchists in the Cerdanya), published by Ediciones Descontrol (editorial@descontrol.cat)

WE FIND IT PROVEN

That the crackdown on priests and right-wingers in the Cerdanya between 20 July 1936 and 8 September 1936 was directed by the mayor of Puigcerdá, Jaime Palau, a member of the ERC (Esquerra).

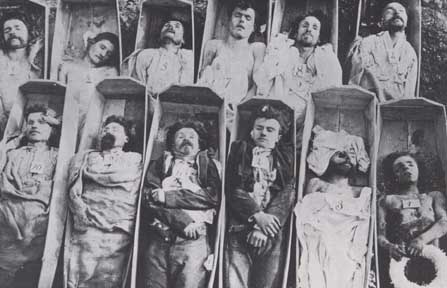

That the list of 21 right-wing Puigcerdá citizens “who had to be eliminated” was thrashed out and drawn up in the Esquerra Republicana de Cataluña Clubhouse and its president Eliseo Font Morera “approved the list of victims”. The persons featuring on the list were arrested and murdered on the night of 9 September 1936.

Then when it came to the establishment of the Puigcerdá Town Administrative Council on 20 October 1936, the anarchists forced the ERC to participate in the shape of the two chief protagonists of the crack-down on rightists: Jaime Palau and Elise Font.

That ANTONIO MARTÍN ESCUDERO, the Durruti of the Cerdanya, was assassinated on the bridge in Bellver on 27 April 1937 in an ambush set by the ERC and Estat Catalá. The murder was due to the anarchists’ steely monitoring of the border, to the detriment of the smuggling activities of stalinists and (Catalan) nationalists.

That, after 10 June 1937, in the wake of the political defeat suffered by the anarchists in the May Events, it was the anarchists’ turn. Seven libertarians were murdered in La Serradora by stalinists and nationalists.

An Executive Committee made up of stalinists and nationalists was set up to coordinate and oversee the crack-down on libertarians in the Cerdanya. That crack-down and the campaign of defamation were closely connected. The massacre on 9 September 1936 and all murders committed in the comarca, plus all thievery and criminality were laid at the door of a wrongly blamed scapegoat: the anarchists. This was a distraction from the criminal culpability of the PSUC–ERC and it criminalized the class enemy: the anarchists.

That the majority of historians lie, manipulate or falsify, some of them unknowingly, but most unconsciously: this is within the very nature and condition of the trade by which they make their living. The bourgeoisie’s Hallowed History is a forgery, concocted to spare the nationalists and stalinists from all blame for the outrages during the early days of the Revolution. One good example would be the prevailing historical writing about Puigcerdá and the Cerdanya, which, for upwards of 80 years now, has successfully concealed the fact that the protagonists of the 1934 coup suffered harsh reprisals at the hands of the pro-Spain rightists (españolistas) in 1935; that that repression provoked the Catalanist coup-makers of 1934 into taking revenge by participating in the abuses and arbitrary acts which followed the July 1936 defeat of the military in Barcelona and across Catalonia. And, in particular, that more than one of them belonged to Estat Catalá, or were, for the most part, known members of the ERC listed in the Causa General as answerable for the local killings.

That the myth of mass shootings in the Tosas Pass, carried out on the instructions of the Puigcerdá Committee, collapses in the face of the emphatic detail in a document in the Causa General which, following the disinterment and analysis of those 26 cadavers, found that most belonged to very young people, some of whom were identified as right-wingers and deserters, slain by the carabineers whilst attempting to cross the border. No mention of Committee nor of firing squads; just carabineers and deserters and in any case these deaths had nothing to do with internal issues in the Cerdanya and ought not to be counted as resulting from social and political conflicts in that comarca.

That it should not escape anyone that the irrefutable demolition of the dark legend surrounding Catalan anarchism in the Cerdanya, and more specifically, the fantastic criminalization of Antonio Martin, in the pages of our book on the Cerdanya, carries significant implications:

A. In 1937 the republican and stalinist authorities were deliberately lying and knowingly concocted that dark legend denigrating Catalan anarchism. It was a powerful political weapon used against the CNT–FAI, as well as the perfect defence against their own crimes; these could be pinned on the anarchists.

B. The bourgeoisie’s historians lie and painstakingly choose from among the documentation held in the archives and thereby become the heirs and successors to the propaganda campaign of denigration and defamation which, for the first time in history, successfully ensured that the genuine social and historical facts were eclipsed and replaced by a different fictional reality conjured up by this campaign of propaganda and infamy.

C. In 1937-1938, Catalan stalinists and nationalists subscribed in the same innate, civilized and ethical way to a radical political racism vis à vis the anarchists, in a muddle of ethnic, cultural, ideological and linguistic prejudices. Anarchists were scorned and de-humanized, so that, in the nationalist and stalinist imagination, they stopped being people and instead became brutes and beasts who could be and deserved to be sacrificed on the altar of the homeland. Just the way the españolista right-wingers had been a few months earlier.

D. All of these monsters, serial killers, vampires and priest-eaters who had popped up all over Catalonia like some virus and whom the historians have described as criminals are deserving of a second look. All the historians are under suspicion of partisanship and sectarianism.

E. Over the summer of 1937, the CNT – as an organization – effectively ceased to exist in the Cerdanya. The brutal anti-libertarian repression was orchestrated by an Executive Committee on which Vicente Climent (PSUC), Juan Bayran Clasli (PSUC), Juan Solé (mayor of Bellver), a Watch officer by the name of Samper and another, unnamed officer, both of them Estat Catalá members, served.

IN CONSEQUENCE OF WHICH WE CONCLUDE:

That history is yet another battle in the class war in progress. We posit the proletariat’s revolutionary history as a counter to the bourgeoisie’s history. Lies are routed by truth; myths and dark legends refuted by archives.

That history as a social science is no longer feasible in academic university institutions, where historians are turned into functionaries subject to the authorities and the established order. Honest, scientific, rigorous History is these days only possible in spite of the academic historians and outside of those institutions.

That the mission of bourgeois History is to weave myths about nationalisms, democratic totalitarianism and capitalist economics in order to persuade us that these are eternal, immutable and immoveable. A perpetual, complacent and a-critical present renders the past banal and demolishes historical awareness. We are shifting from Hallowed History towards post-history. Post-truth is a newspeak for a (these days frequent) situation wherein the reporter creates public opinion by bending facts and reality to suit emotions, prejudices, ideologies, propaganda, material interests and politics. If something seems true and in addition flatters one’s vanity or is satisfying emotionally, as well as bolstering prejudices or identity, it deserves to be true. A decent advertising campaign turns lies, fraud and the counterfeit into a palatable, convenient post-truth. Post-history is no longer the narration or interpretation of events that happened in the past, and is turning into a narrative that hacks of every hue and ideology concoct for the publishing market, regardless of facts and historical reality, which are now regarded as being merely symbolic, secondary, dispensable, prejudicial or hidden.

AS A RESULT WE DEMAND:

That the informational panels erected on the bridge in Bellver be removed or amended.

That the ERC claim its share of the responsibility for the killings in Puigcerdá on 9-9-1936 and drop the slanders that that organization has been constantly and systematically peddling against libertarians.

That Pous and Sabaté formally acknowledge their errors and shortcomings, and do so publicly and openly, for the sake of their own self-respect and because it is only fair.

WE ARE EMBARKING UPON the dissemination of this text with the aim of alerting libertarians and dispelling and freeing them from the huge moral damage they have endured because of this degrading defamatory campaign, driven by the nationalists and stalinists.

There can be no compact or collaboration with the class enemy. We invite the inevitably minority of anarchists and rebels, armed with principles, even though they have no homeland and no flags, no gods and no frontiers, not to give up nor give in, but to associate themselves with these demands by sending messages of support for this Manifesto to the HISTORY DEFENCE COMMITTEE, e-mail: chbalance@gmail.com

Antonio Gascón and Agustín Guillamón, Puigcerdá, 27 April 2018