This is the next installment from the Anarchist Current, the Afterword to Volume Three of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, in which I survey the historical origins and development of anarchist ideas. In this installment, I discuss anarchist views during the 1880s-1890s on the relationship between means and ends and the need to remain engaged in popular struggles. I briefly refer to the execution on November 11, 1887, of the Haymarket Martyrs, four Chicago anarchists framed for a bombing at a demonstration against police violence at the beginning of May 1886. I previously posted one of Voltairine de Cleyre‘s speeches commemorating their executions and excerpts from their trial speeches.

In Britain and several of its former colonies, November 11th is celebrated as a day of remembrance for all the soldiers who have been killed fighting wars on behalf of their political and economic masters. Earlier this year I posted the International Anarchist Manifesto against the First World War. I have also posted Marie Louise Berneri’s critique of the hypocrisy of the politicians and patriots who condemn any acts of violence against the existing order as “terrorism” but venerate the mass slaughters known as “modern warfare” as great patriotic self-sacrifice.

Means and Ends

There were ongoing debates among anarchists regarding methods and tactics. Cafiero agreed with the late Carlo Pisacane that “ideals spring from deeds, and not the other way around” (Volume One, Selections 16 & 44). He argued that anarchists should seize every opportunity to incite “the rabble and the poor” to violent revolution, “by word, by writing, by dagger, by gun, by dynamite, sometimes even by the ballot when it is a case of voting for an ineligible candidate” (Volume One, Selection 44).

Kropotkin argued that by exemplary actions “which compel general attention, the new idea seeps into people’s minds and wins converts. One such act may, in a few days, make more propaganda than thousands of pamphlets” (1880).

Jean Grave (1854-1939) explained that through propaganda by the deed, the anarchist “preaches by example.” Consequently, contrary to Cafiero, “the means employed must always be adapted to the end, under pain of producing the exact contrary of one’s expectations”. For Grave, the “surest means of making Anarchy triumph is to act like an Anarchist” (Volume One, Selection 46). Some anarchists agreed with Cafiero that any method that brought anarchy closer was acceptable, including bombings and assassinations. At the 1881 International Anarchist Congress in London, the delegates declared themselves in favour of “illegality” as “the only way leading to revolution” (Cahm: 157-158), echoing Cafiero’s statement from the previous year that “everything is right for us which is not legal” (Volume One, Selection 44).

After years of state persecution, a small minority of self-proclaimed anarchists adopted terrorist tactics in the 1890s. Anarchist groups had been suppressed in Spain, Germany and Italy in the 1870s, particularly after some failed assassination attempts on the Kaiser in Germany, and the Kings of Italy and Spain in the late 1870s, even before Russian revolutionaries assassinated Czar Alexander II in 1881. Although none of the would be assassins were anarchists, the authorities and capitalist press blamed the anarchists and their doctrine of propaganda by the deed for these events, with the Times of London describing anarchism in 1879 as having “revolution for its starting point, murder for its means, and anarchy for its ideals” (Stafford: 131).

Those anarchists in France who had survived the Paris Commune were imprisoned, transported to penal colonies, or exiled. During the 1870s and 1880s, anarchists were prosecuted for belonging to the First International. In 1883, several anarchists in France, including Kropotkin, were imprisoned on the basis of their alleged membership, despite the fact that the anti-authoritarian International had ceased to exist by 1881. At their trial they declared: “Scoundrels that we are, we claim bread for all, knowledge for all, work for all, independence and justice for all” (Manifesto of the Anarchists, Lyon 1883).

Perhaps the most notorious persecution of the anarchists around this time was the trial and execution of the four “Haymarket Martyrs” in Chicago in 1887 (a fifth, Louis Lingg, cheated the executioner by committing suicide). They were convicted and condemned to death on trumped up charges that they were responsible for throwing a bomb at a demonstration in the Chicago Haymarket area in 1886.

When Emile Henry (1872-1894) threw a bomb into a Parisian café in 1894, describing his act as “propaganda by the deed,” he regarded it as an act of vengeance for the thousands of workers massacred by the bourgeoisie, such as the Communards, and the anarchists who had been executed by the authorities in Germany, France, Spain and the United States. He meant to show to the bourgeoisie “that those who have suffered are tired at last of their suffering” and “will strike all the more brutally if you are brutal with them” (1894). He denounced those anarchists who eschewed individual acts of terrorism as cowards.

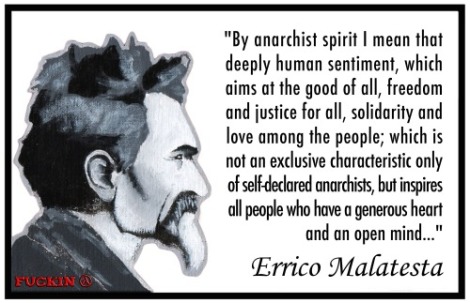

Malatesta, who was no pacifist, countered such views by describing as “ultra-authoritarians” those anarchists who try “to justify and exalt every brutal deed” by arguing that the bourgeoisie are just “as bad or worse.” By doing so, these self-described anarchists had entered “on a path which is the most absolute negation of all anarchist ideas and sentiments.” Although they had “entered the movement inspired with those feelings of love and respect for the liberty of others which distinguish the true Anarchist,” as a result of “a sort of moral intoxication produced by the violent struggle” they ended up extolling actions “worthy of the greatest tyrants.” He warned that “the danger of being corrupted by the use of violence, and of despising the people, and becoming cruel as well as fanatical prosecutors, exists for all” (Volume One, Selection 48).

In the 1890s, the French state brought in draconian laws banning anarchist activities and publications. Bernard Lazare (1865-1903), the writer and journalist then active in the French anarchist movement, denounced the hypocrisy of the defenders of the status quo who, as the paid apologists for the police, rationalized the far greater violence of the state. He defiantly proclaimed that no “law can halt free thought, no penalty can stop us from uttering the truth… and the Idea, gagged, bound and beaten, will emerge all the more lively, splendid and mighty” (Volume One, Selection 62).

Malatesta took a more sober approach, recognizing that “past history contains examples of persecutions which stopped and destroyed a movement as well as of others which brought about a revolution.” He criticized those “comrades who expect the triumph of our ideas from the multiplication of acts of individual violence,” arguing that “bourgeois society cannot be overthrown” by bombs and knife blows because it is based “on an enormous mass of private interests and prejudices… sustained… by the inertia of the masses and their habits of submission.” While he argued that anarchists should ignore and defy anti-anarchist laws and measures where able to do so, he felt that anarchists had isolated themselves from the people. He called on anarchists to “live among the people and to win them over… by actively taking part in their struggles and sufferings,” for the anarchist social revolution can only succeed when the people are “ready to fight and… to take the conduct of their affairs into their own hands” (Volume One, Selection 53).

Robert Graham

Additional References

Cahm, Caroline. Kropotkin and the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism, 1872-1886. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Henry, Emile. “A Terrorist’s Defence” (1894). The Anarchist Reader. Ed. G. Woodcock. Fontana, 1977.

Kropotkin, Peter. “The Spirit of Revolt” (1880). Kropotkin’s Revolutionary Pamphlets. Ed. R.N. Baldwin. New York: Dover, 1970.

Stafford, David. From Anarchism to Reformism: A Study of the Political Activities of Paul Brousse, 1870-90. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971.

Leave a comment