Last year, I posted a series of writings by anarchist and revolutionary socialist participants in the international workers’ movement and the 1871 Paris Commune. This month marks the (142nd) anniversay of the tragic defeat of the revolutionary Paris Commune, which became an inspiration to thousands of anarchists and revolutionaries across the globe. Today, I have created a page setting forth the various writings on the Commune previously posted separately, which you can access by clicking here. Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas has a chapter on the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, with writings by Bakunin, Louise Michel and Kropotkin.

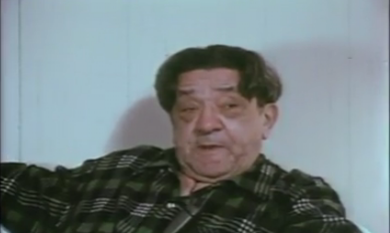

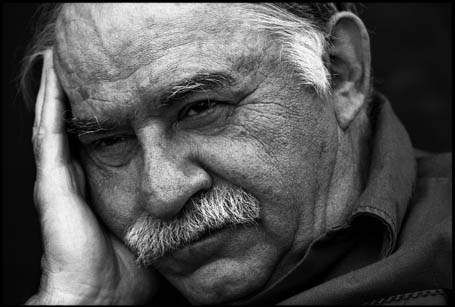

Murray Bookchin: Anarcho-Communalism (1981)

In September 1981, the Open Road editorial collective in Vancouver interviewed Murray Bookchin while he was finishing his magnum opus, The Ecology of Freedom (yes, the legend is true: he spent some of his time correcting the galley proofs in a local MacDonald’s). The publication of The Ecology of Freedom in 1982 marked the apogee of Bookchin’s eco-anarchism. After that he came to focus more on his concept of “libertarian municipalism,” eventually rejecting anarchism altogether. Back in 1981, Bookchin was an anarchist, and proud of it. The interview was published in the Spring 1982 issue of Open Road, No. 13. This is the first of two parts. Space limitations prevented me from including excerpts from this interview in Volume Three of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, now available from AK Press. Volume Three does include Bookchin’s essay, “Toward an Ecological Society,” which summarizes the main themes in The Ecology of Freedom.

Murray Bookchin: My concern is to develop a North American type of anarchism that comes out of the American tradition, or that at least can be communicated to Americans and that takes into consideration that Americans are not any longer people of European background. Another consideration is to find out what is the real locus of libertarian activity. Is it the factory? Is it the youth? Is it the schools? Is it the community?

The only conclusion I could arrive at with the death of the workers’ movement as a revolutionary force—you know the imagery of the proletarian vanguard, or proletarian hegemony—has been the community.

I’ve tried to start up from a different perspective involving a broader ecological perspective perhaps, and more or less updating my thinking historically, to many of the ideas expressed in Mutual Aid by Kropotkin (which doesn’t mean I’m a Kropotkinite). And I’ve gone toward an idea which in fact Kropotkin played around with a great deal, and which unfortunately acquired a bad name because it was associated with a French anarchist, Paul Brousse, who became a reformist…

I’ve followed Brousse’s career very carefully and I don’t know that you necessarily have to wind up in the type of situation where Brousse did. And that is to restore the image of the commune, the revolutionary commune, the neighbourhoods, the townships, in which the factories at best would be part of the community, not the factories usurping the community. This is anarcho-communalism in the full sense of the word. Thus I would like to believe that the arena would be an attempt to restore the revolutionary communal situation that existed in the 19th century and that I think can exist today even though we have tremendous crisis and division in the cities.

The goal would be basically to try to revive civic organizations which would aim for the municipalization, the equivalent of collectivization of industry, of land, and create assemblies in the smaller communities, or many such assemblies federated in the larger communities.

As for the workers’ movement, I find that I reach workers more easily as neighbours than I do standing outside the factory despairingly giving out a leaflet telling them to take over, say the Ford plant. This doesn’t mean, of course, that you may not have worker’s movements developing, but the real question is whether or not one is going to have a unionist orientation or a communal orientation, whether the factories link with factories or the factories link with the people in the community. This is reinforced in my opinion by my conviction that the American middle class is being wiped out. In fact I believe that’s probably going to happen in much of North America through inflation, taxation…

Open Road: One of the obstacles to a municipal or community movement in North America would be the absolute lack of community in this society. There’s no interaction among people in neighhourhoods anymore.

Bookchin: Admittedly that’s so, but the problem of reviving it is another issue that has to be discussed. How about trying to revive it? I can’t think of any other arena in which to function as an anarchist.

Open Road: What about the alternative of rather than working within an existing geographical community, stepping outside of that whole grouping with one’s peers and building a base—rather than starting from within and all the compromises that would entail?

Bookchin: That’s one way of looking at it. And another way is starting from within but not within institutions, but creating counter institutions in their own community. Suppose you have food co-ops that interlink with, possibly, alternative schools. This is purely hypothetical. Right now there is a great deal of passivity; people are watching and waiting. And there is a very strong feeling of powerlessness. So, admittedly, if you were to point to institutions that exist right now in North America, or for that matter to a great extent in Europe, I would certainly agree with you. There is nothing to work with. But the point is what could we work with, or what could we try to create. And one of the things we can try to create would be the food co-ops, the health centres, the women’s centres, educational centres, even protective centres for elderly people in crime-ridden areas. In some instances even certain social services that normally were supplied, or pre-empted by the state. Take the United States, the Reagan administration is withdrawing assistance, all kinds of welfare programs, and if people don’t improvise their own resources to cope with problems of the ageing, problems of the sick, problems of the young, problems of the poor, problems of tenant rights, who will? And out of this may come the possibility of creating counter institutions, which I don’t believe in and of themselves are going to replace the existing institutions, but could be a dropping off point for the development of attitudes, techniques, and the practice of self-management.

Open Road: Getting back to libertarian municipalism, what you’re emphasizing is creating decentralized, democratic assemblies?

Bookchin: Yes. You see my residence is in New England, and New England has a strong tradition of localism. What is ordinarily called election day in most of the United States is called town meeting day in Vermont. And there are town meetings that are to one degree or another active, however vestigial their powers. They, for example, banned uranium mining in the Green Mountains of Vermont. And the governor of the state was forced to knuckle down to that even though he wanted uranium mining. A number of town meetings—not very large a number but at least a majority of those who had it on their agenda—voted for a nuclear arms moratorium. They’re taking up issues like that at town meetings. What we would like to do if we could is foster, at least in Vermont, greater local power, discussions around issues that are not simply immediate local issues. We would like to raise broad issues at these town meetings and turn them into discussion arenas and interlink the various assemblies and town meetings or try to help create growth of this type of local municipal power—communal power—a view toward, very frankly, establishing a grass-roots self-management institutional framework or network. Now this may be a pure dream, a hopeless ideal, but it’s meaningless for us to go to factories, I can tell you that much.

For me it’s meaningless to function in a very large city like New York, because I don’t think that one should measure the social weight of an area by the number of people it has. I think it should be measured by the quality of the politics involved. New York has a tremendous number of people but the quality of its politics is unspeakable. By contrast, in a smaller township, I find there’s a great deal of social awareness, less of a sense of powerlessness, less of a polarization of economic life. More people have been affected, in an amusing sense, by the fact that Burlington elected a socialist mayor—and I’m not concerned with elections at the moment: I’m concerned with what are called impacts—than they are by a demonstration for El Salvador in New York.

Open Road: One thing you mentioned is the danger of counter-institutions and projects becoming co-opted. Couldn’t they be used to supplement deteriorating social services and merely obscure the real nature of the state?

Bookchin: Yeah, that could happen. And that’s why I think an anarchist consciousness is necessary and why an anarchist movement is necessary. There is nothing that can’t be, at least hypothetically, co-opted, including anarchism. I’ve seen the professionalization of anarchism in a number of universities. That’s not what I’m saying. What I’m addressing myself to is an anarchist theory of community and community activities. I’m not speaking of these things just occurring without any consciousness, intuitively or instinctively, merely in reaction to things that the state power does.

My feeling is that anarchists have to think in terms of a specific. I think the dispersal of anarchists all over the place, particularly very gifted ones who can turn out periodicals and do very effective public work, and their tendency to just pick up and take off is a liability. What I’m trying to do in Burlington is to help foster the development of a group of anarchists who will pick up on American radical tradition, or confederal traditions which might even exist in Canada as well. And I’m more interested in seeing some good examples established here, there and anywhere, than I am in seeing an attempt to build mass movements that in fact involve the dissolution of almost any movement in an amorphous mass that is politically very passive.

Open Road: What authentic North American radical traditions can you see us building on?

Bookchin: What I’d like to see developing is an American radicalism, libertarian in character, which relies, however weak, faint, and even mythic these traditions may be, on the American libertarian tradition. I don’t mean right-wing libertarianism obviously. I’m talking of the idea, basically very widespread in America, that the less government the better, which is obviously being used to the advantage of the big corporations, but none-the-less has very radical implications. The idea of a people that exercises a great deal of federalist or confederalist control, the ideal of a grass-roots type of democracy, the idea of the freedom of the individual which is not to get lost in the mazes of anarcho-egotism à la Stirner, or for that matter right-wing libertarianism. So I feel that now we have some opportunity in North America to go back and say the American Revolution was the real thing. I don’t want to think any longer simply in terms of the Spanish Revolution or the Russian Revolution. It doesn’t make any sense to talk Makhno to an American.

Open Road: What sort of activities would you suggest that conscious anarchists be doing?

Bookchin: At this point in North America the most important thing they can do is educate themselves, develop a propaganda machinery in the form of books and periodicals, a literature, engage in discussion groups that are open to a community, to discuss and develop their ideas and to develop networks. I think it’s terribly important that networks of anarchists establish themselves with a view toward educating people. In my case I would emphasize anarcho-communalism, along with the ecological questions, the feminist questions, the anti-nuclear issues that exist, and along with the articulation of popular institutions in the community. I think it’s terribly important for anarchists to do that because at this moment not very much is happening anywhere in North America. This may be a period of time, and a very valuable period of time of preparation, intellectually, emotionally and organizationally. My main interests right now are to publish, to write, to explicate various views which I hope have an impact on thinking people.

I know one thing: that you can do a lot of things but if you don’t educate people into conscious anarchism it gets frittered away. In the 60s there were a lot of things which were anarchistic. May-June ‘68 was riddled by anarchistic sentiments, dreams and ideals, but insofar as this was not strengthened organizationally and intellectually by a very effective, powerful infrastructure, then what happens is the movement becomes dissipated.

Best of Social Anarchism

Just got my copy of The Best of Social Anarchism, a collection of articles and reviews from Social Anarchism, the US published review that has been coming out since 1980. It has some great stuff in it, some of which I had forgotten about, including a critical survey of the so-called “new anarchism” by Brian Morris, not to be confused with Volume Three of my anthology, Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, The New Anarchism (1974-2012). The only article in both anthologies is Jeff Ferrell’s “Against the Law: Anarchist Criminology,” so there isn’t much overlap, which is nice. It’s very reasonably priced, and covers a very wide range of topics showing the continuing relevance of anarchism today.

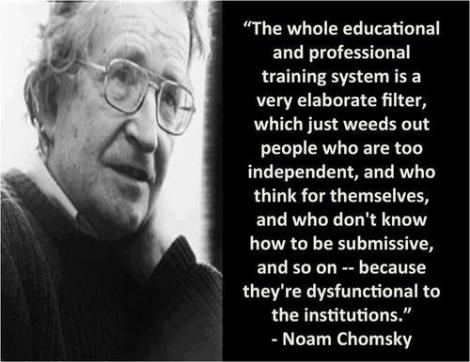

The Best of Social Anarchism also includes my essay on “Chomsky’s Contributions to Anarchism,” which was part of a special issue of Social Anarchism marking the publication of Chomsky on Anarchism, edited by Barry Pateman, a collection of essays by and interviews with Noam Chomsky focusing on anarchist related topics. The introductory note to my piece on Chomsky incorrectly identifies it as the introduction to Chomsky on Anarchism, which was actually written by Barry Pateman. The introductory note also makes my essay on Chomsky sound much more critical than it really is (see for yourself by clicking this link).

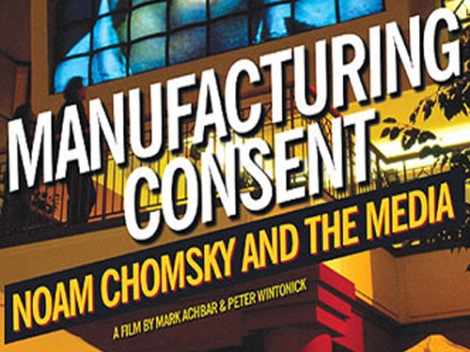

I don’t “divorce” Chomsky’s linguistic ideas from any relevance to political ideology but simply quote his own remarks to the effect that his linguistic theories are only “suggestive as to the form that a libertarian social theory might assume.” Some of the political implications of his linguistic theories are drawn out by Chomsky himself in one of the selections I included in Volume Three of the Anarchism anthology, under the title “Human Nature and Human Freedom” (which incidentally is not included in Chomsky on Anarchism). When I suggest that perhaps Chomsky’s most lasting contribution to radical political theory is his analysis and critique of the role of the media and intellectuals in modern society, “manufacturing the consent” of the general population to their own exploitation, I refer to Chomsky’s own acknowledgement that much of this critique originated with the anarchist revolutionary, Michael Bakunin, who warned that rule by intellectuals would constitute “the most aristocratic, despotic, arrogant and elitist of all regimes.”

My description of Chomsky as an anarchist “fellow-traveller” is again a quote from Chomsky, not my description. I also give credit to Chomsky for introducing many people, including myself, to anarchist ideas, particularly the constructive achievements of the anarchists in the Spanish Revolution and Civil War. My comment that Chomsky’s contributions to specifically anarchist ideas are modest is consistent with Chomsky’s own self-evaluations, and not an attempt to belittle his role in making anarchist ideas better known to the general public.