With today’s massacre of the writers and artists at Charlie Hebdo in Paris, it is worth reflecting on the price people have paid, and continue to pay, for freely expressing themselves. Anarchists are no strangers to persecution, and even death, for expressing their views. The Haymarket Martyrs were executed on November 11, 1887 for advocating armed struggle and revolution. Countless Communards were massacred during the suppression of the Paris Commune for defending their federalist ideals. Gustav Landauer was murdered during the 1919 Bavarian Revolution for his communitarian anarchist socialism. Francisco Ferrer was shot in 1909 for advocating libertarian education. Ricardo Flores Magon died in a U.S. prison in 1922 for advocating anarchy during the Mexican Revolution. Peter Arshinov and other Russian anarchists were shot by the Communists in Russia. Camillo Berneri was murdered by Stalinists during the Spanish Revolution and Civil War. Kotoku Shusui, Osugi Sakae and Ito Noe were murdered by the Japanese authorities. The Korean anarchist, Shin Chaeho, died in a Japanese prison camp. Louise Michel and Voltairine de Cleyre’s deaths were hastened by shots to the head from people who detested their ideas. Many more have died for their ideas, and many more still have been imprisoned for them, including Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta, Grave, Galleani, Reclus, Most, Goldman, Berkman, Maksimov and too many others to mention. Today anarchists are persecuted and imprisoned under “anti-terrorist” laws, laws which are designed more to protect the powers that be than ordinary people. Which brings me to my latest installment from the “Anarchist Current,” the afterword to Volume Three of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. In this excerpt, I discuss anarchist views on art, anarchy and authority.

Art and Anarchy

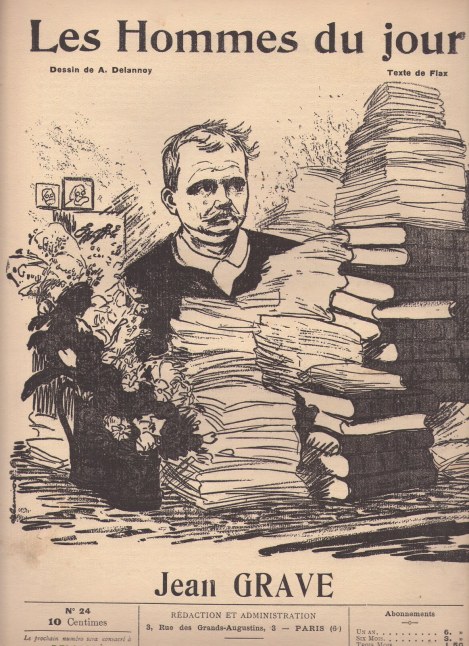

The English anarchist, Charlotte Wilson, argued that when “each worker will be entirely free to do as nature prompts… to throw his whole soul into the labour he has chosen, and make it the spontaneous expression of his intensest purpose and desire… labour becomes pleasure, and its produce a work of art” (Volume One, Selection 37). For artists in bourgeois society, Jean Grave observed that they must sell their works to survive, “a situation which leads those who would not die of hunger to compromise, to vulgar and mediocre art.” To “live their dream, realize their aspirations, they, too, must work” for the social revolution. Even when possible, it “is vain for them to entrench themselves behind the privileges of the ruling classes,” for “if there is debasement for him who is reduced to performing the vilest tasks to satisfy his hunger, the morality of those who condemn him to it is not superior to his own; if obedience degrades, command, far from exalting character, degrades it also” (Volume One, Selection 63).

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), who for a time described himself as an anarchist, agreed with Grave, in The Soul of Man Under Socialism, that with the abolition of private property, all will be free “to choose the sphere of activity that is really congenial to them, and gives them pleasure.” However, Wilde did not look forward to the day when manual and intellectual labour would be combined, for some forms of manual labour are so degrading that they cannot be performed with dignity or joy: “Man is made for something better than disturbing dirt. All work of that kind should be done by machine.”

Wilde spoke in favour of anarchist socialism as providing the basis for true individualism and artistic freedom. He believed that the only form of government suitable to the artist “is no government at all. Authority over him and his art is ridiculous,” whether exercised by a government or by public opinion (Volume One, Selection 61). Wilson agreed that public opinion, “the rule of universal mediocrity,” is “a serious danger to individual freedom,” but in a free society “it can only be counteracted by broader moral culture” (Volume One, Selection 37). For Wilde, this meant that “Art should never try to be popular. The public should try to make itself artistic” (Volume One, Selection 61).

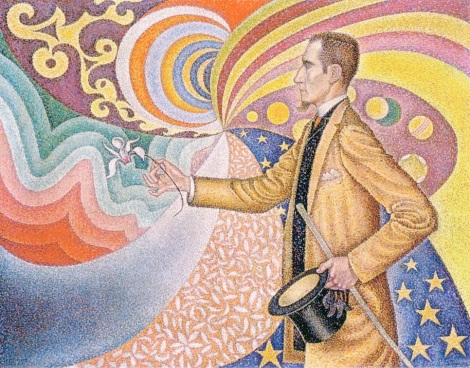

In turn of the century France, much of the artistic avant-garde allied themselves with anarchism, including such painters as Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac, Charles Maurin and Maximilien Luce, and writers like Paul Adam, Adolphe Retté, Octave Mirbeau and Bernard Lazare. Jean Grave would include their work in his anarchist papers, La Révolte, and later, Les Temps Nouveaux. When the French authorities again prosecuted anarchists simply for expressing their subversive ideas in the mid-1890s, Lazare wrote in La Révolte: “We had the audacity to believe that not everything was for the best in the best of all possible worlds, and we stated and state still that modern society is despicable, founded upon theft, dishonesty, hypocrisy and turpitude” (Volume One, Selection 62).

As can be seen, the anarchist critique of existing society was never limited to denouncing the state, capitalism and the church. It extended to the patriarchal family, the sexual exploitation and subjection of women, censorship, conformism, authoritarian education, and hierarchical and coercive forms of organization in general, no matter where they might be found, whether in the school, at the workplace or within the revolutionary movement itself.

Robert Graham

[…] https://robertgraham.wordpress.com/2015/01/07/art-and-anarchy/ […]