Returning to my series from the Anarchist Current, the Afterword to Volume Three of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, this installment deals with the effect of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune on anarchist theory and practice.

The Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune

The Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune of 1870-1871 had a significant impact on emerging anarchist movements. Bakunin argued that the War should be turned into a mass uprising by the French workers and peasants against their domestic and foreign masters. To bring the peasants over to the side of the social revolution, Bakunin urged his fellow revolutionaries to incite the peasantry “to destroy, by direct action, every political, judicial, civil and military institution,” to “throw out those landlords who live by the labour of others” and to seize the land. He rejected any notion of revolutionary dictatorship, warning that any attempt “to impose communism or collectivism on the peasants… would spark an armed rebellion” that would only strengthen counter-revolutionary tendencies (Volume One, Selection 28).

Although it was Proudhon who had first proposed an alliance between the workers and peasants, it was Bakunin who saw the peasantry as a potentially revolutionary force. Bakunin and subsequent anarchists did not believe that a social revolution was only possible in advanced capitalist societies with a large industrial proletariat, as Marxists claimed, but rather looked to the broad masses of the exploited and downtrodden to overthrow their oppressors. Consequently, anarchists supported the efforts of indigenous peoples to liberate themselves from colonial domination and the local elites which benefitted from colonialism at their expense, particularly in Latin America with its feudalist latifundia system which concentrated ownership of the land in the hands of a few (Volume One, Selections 71, 76 & 91). In Russia, Italy, Spain and Mexico, anarchists sought to incite the peasants to rebellion with the battle cry of “Land and Liberty” (Volume One, Selections 71, 73, 85, 86, & 124), while anarchists in China, Japan and Korea sought the liberation of the peasant masses from their feudal overlords (Volume One, Selections 97, 99, 101, 104 & 105).

Bakunin argued that the best way to incite the masses to revolt was “not with words but with deeds, for this is the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda” (Volume One, Selection 28). In Mexico, the anarchist Julio Chavez Lopez led a peasant uprising in 1868-1869, in which the insurgents would occupy a village or town, burn the land titles and redistribute the land among the peasants (Hart: 39). In September 1870, Bakunin participated in a short-lived attempt to create a revolutionary Commune in Lyon, proclaiming the abolition of mortgages and the judicial system (Leier: 258). He made a similar attempt with his anarchist comrades in Bologna in 1874.

In 1877, Bakunin’s associates, Carlo Cafiero (1846-1892), Errico Malatesta (1853-1932) and a small group of anarchists tried to provoke a peasant uprising in Benevento, Italy, by burning the local land titles, giving the villagers back their tax moneys and handing out whatever weapons they could find. Paul Brousse (1844-1912) described this as “propaganda by the deed,” by which he did not mean individual acts of terrorism but putting anarchist ideas into action by seizing a commune, placing “the instruments of production… in the hands of the workers,” and instituting anarchist communism (Volume One, Selection 43).

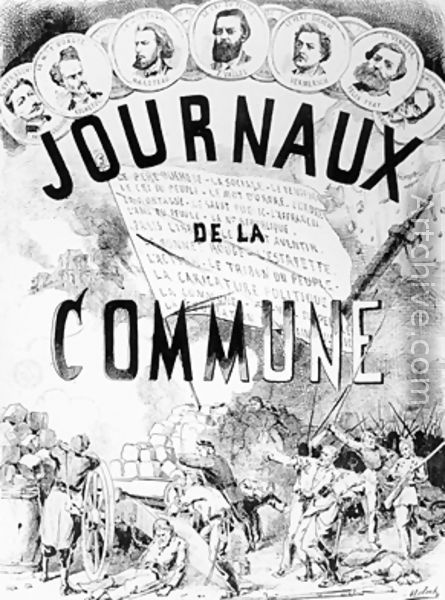

The inspiration for this form of propaganda by the deed was the Paris Commune of 1871, when the people of Paris proclaimed the revolutionary Commune, throwing out their national government. Varlin and other Internationalists took an active part in the Commune. After its bloody suppression by the Versailles government, during which Varlin was killed, several Communards were to adopt an explicitly anarchist position, including Elisée Reclus and Louise Michel.

The anti-authoritarian sections of the First International supported the Commune and provided refuge for exiled Communards. Bakunin commended the Communards for believing that the social revolution “could neither be made nor brought to its full development except by the spontaneous and continued action of the masses” (Volume One, Selection 29). James Guillaume thought that the Commune represented the revolutionary federalist negation of the nation State that “the great socialist Proudhon” had been advocating for years. By 1873, the Jura Federation of the International was describing the Commune as the first practical realization of the anarchist program of the proletariat. However, as David Stafford points out, the “massacre of the Communards and the savage measures which followed it (it has been estimated that 30,000 people were killed or executed by the Versailles forces)” helped turn anarchists further away from Proudhon’s pacifist mutualism, which was seen as completely unable to deal with counter-revolutionary violence (Stafford: 20).

Louise Michel (1830-1905) had fought on the barricades when the French government sent in its troops to put down the Commune. The Union of Women for the Defence of Paris and the Care of the Wounded issued a manifesto calling for “the annihilation of all existing social and legal relations, the suppression of all special privileges, the end of all exploitation, the substitution of the reign of work for the reign of capital” (Volume One, Selection 30). At Michel’s trial after the suppression of the Commune, she declared that she belonged “completely to the Social Revolution,” vowing that if her life were spared by the military tribunal, she would “not stop crying for vengeance,” daring the tribunal, if they were not cowards, to kill her (Volume One, Selection 30).

Anarchists drew a number of lessons from the Commune. Kropotkin argued that the only way to have consolidated the Commune was “by means of the social revolution” (Volume One, Selection 31), with “expropriation” being its “guiding word.” The “coming revolution,” Kropotkin wrote, would “fail in its historic mission” without “the complete expropriation of all those who have the means of exploiting human beings; [and] the return to the community… of everything that in the hands of anyone can be used to exploit others” (Volume One, Selection 45).

With respect to the internal organization of the Commune, Kropotkin noted that there “is no more reason for a government inside a commune than for a government above the commune.” Instead of giving themselves a “revolutionary” government, isolating the revolutionaries from the people and paralyzing popular initiative, the task is to abolish “property, government, and the state,” so that the people can “themselves take possession of all social wealth so as to put it in common,” and “form themselves freely according to the necessities dictated to them by life itself” (Volume One, Selection 31).

Robert Graham

Additional References

Hart, John M. Anarchism and the Mexican Working Class, 1860-1931. Austin: University of Texas, 1987.

Leier, Mark. Bakunin: The Creative Passion. New York: Thomas Dunne, 2006.

Stafford, David. From Anarchism to Reformism: A Study of the Political Activities of Paul Brousse, 1870-90. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971.

Reblogged this on Fahrenheit 451 Used Books and commented:

Left Wing Books, Blogs, Video’s fah451bks.wordpress.com Leadership, Education, Solidarity, Struggle, Sacrifice “Serve the People”