This is the third installment from The Anarchist Current, the Afterword to Volume Three of my anthology of anarchist writings, Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, in which I discuss the origins and development of anarchist ideas from ancient China to the present day. Part one dealt with Daoism and anarchism in China around 300 CE. Part two dealt with Etienne de la Boetie’s critique of voluntary servitude and various religious heresies, from the Mu‘tazili Muslims to the Diggers in the English Revolution and Civil War. Part three deals with anarchist currents in Europe leading up to and during the Great French Revolution of 1789-1795.

Utopian Undercurrents

Hounded by both parliamentary and royalist forces, the Digger movement did not survive the English Civil War. However, anarchist ideas continued to percolate underground in Europe, resurfacing during the Enlightenment and the 1789 French Revolution.

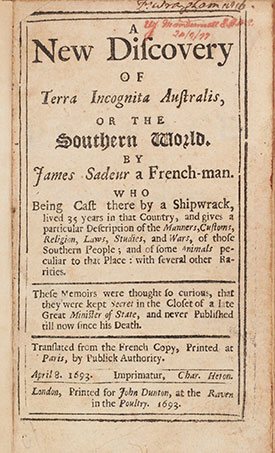

In 1676, Gabriel de Foigny, a defrocked priest, published in Geneva Les Adventures de Jacques Sadeur dans la découverte de la Terre Australe, in which he depicted an imaginary society in Australia where people lived without government, religious institutions or private property. De Foigny was considered a heretic and imprisoned. A year after his death in 1692, an abridged English translation of Les Adventures appeared as A New Discovery of Terra Incognita Australis. According to Max Nettlau, de Foigny’s book became “well known,” being “reprinted and translated many times” (1996: 12).

Jean Meslier, a priest from the Champagne area of France, wrote a political Testament in the 1720s in which he denounced the alliance of Church and State, calling on the people to keep for themselves “all the riches and goods you produce so abundantly with the sweat of your brow,” and to let “all the great ones of the earth and all nobles hang and strangle themselves with the priests’ guts” (Joll: 14). Similar sentiments were expressed by the French philosophe, Denis Diderot, who wrote in 1772 that “nature has made neither servant nor master—I want neither to give nor to receive laws… weave the entrails of the priest, for want of a rope, to hang the kings” (Berneri: 202). During the French Revolution this was transformed into the slogan, “Humanity will not be happy until the last aristocrat is hanged by the guts of the last priest.” Many variations on this slogan have followed since, with the Situationists during the May-June 1968 events in France calling for the last bureaucrat to be hanged by the guts of the last capitalist (Knabb: 344).

On the eve of the French Revolution of 1789, Sylvain Maréchal (1750-1803) published some fables and satirical works evincing an anarchist stance, picturing in one “the life of kings exiled to a desert island where they ended up exterminating each other” (Nettlau: 11). He attacked religion and promoted atheism. In 1796, in the face of the growing reaction, he published his “Manifesto of the Equals” (Volume One, Selection 6), in which he called on the people of France to march over the bodies of “the new tyrants, seated in the place of the old ones,” just as they had “marched over the bodies of kings and priests.” Maréchal sought “real equality,” through “the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth,” and the abolition not only of “individual property in land,” but of “the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed.”

The Great French Revolution

Anarchist tendencies emerged among the more radical elements during the first, or “Great,” French Revolution of 1789, particularly among the sans-culottes and enragés who formed the backbone of the Revolution. Denounced as anarchists by their opponents, they did not entirely reject the label. In 1793, the sans-culottes of Beaucaire identified their allies as “those who have delivered us from the clergy and nobility, from the feudal system, from tithes, from the monarchy and all the ills which follow in its train; those whom the aristocrats have called anarchists, followers of faction (factieux), Maratists” (Joll: 27).

The sans-culottes played an important role in the revolutionary “sections” in Paris, directly democratic neighbourhood assemblies through which ordinary people took control of their lives. As Murray Bookchin has argued, the sections “represented genuine forms of self-management” that “awakened a popular initiative, a resoluteness in action, and a sense of revolutionary purpose that no professional bureaucracy, however radical its pretensions, could ever hope to achieve” (Volume Two, Selection 62).

Unfortunately, other forces on the left, notably Robespierre and the Jacobins, adopted an authoritarian policy of revolutionary terror to fight the counter-revolution, leading the enragé Jean Varlet (1764-1837) to denounce so-called “revolutionary government” as a monstrous “masterpiece of Machiavellianism” that purported to put the revolutionary authorities “in permanent insurrection” against themselves, which is patently absurd (Volume One, Selection 5).

Varlet and other sans-culottes and enragés had fought with the Jacobins against the more conservative Girondins, unwittingly helping the Jacobins to institute their own dictatorship. When Varlet saw his fellow revolutionaries “clapped in irons” by the Jacobins, he “retreated back into the ranks of the people” rather than support “a disgusting dictatorship dressed up with the title of Public Safety.” He could not accept that “Robespierre’s ghastly dictatorship” could somehow vindicate the preceding dictatorship of the Girondins, nor that he and his fellow enragés could be blamed for being the unwitting dupes of the Jacobins, claiming that they had done “nothing to deserve such a harsh reproach” (Volume One, Selection 5).

Varlet made clear that the Jacobin policy of mass arrests and executions, the so-called “Reign of Terror,” far from protecting the gains of the revolution, was not only monstrous but counter-revolutionary, with “two thirds of citizens” being deemed “mischievous enemies of freedom” who “must be stamped out,” terror being “the supreme law” and torture “an object of veneration.” The Jacobin terror “aims to rule over heaps of corpses” under the pretext that “if the executioners are no longer the fathers of the nation, freedom is in jeopardy,” turning the people against the revolution as they themselves become its victims. Even with the overthrow of Robespierre in July 1794, Varlet warned that “his ghastly system has survived him,” calling on the French people to take up their arms and their pens to overthrow the government, whatever its revolutionary pretensions.

Varlet, in rejecting his own responsibility for the Jacobin ascendancy to power, avoided a critique of revolutionary violence, simply calling on the people to rise yet again against their new masters, a call which went largely unanswered after years of revolutionary upheaval which had decimated the ranks of the revolutionaries and demoralized the people. There were a couple of abortive uprisings in Paris in 1795, but these were quickly suppressed.

Robert Graham

Additional References

Berneri, Marie Louise. Journey Through Utopia. London: Routlege & Kegan Paul, 1950 (republished by Freedom Press, 1982).

Joll, James. The Anarchists. 2nd Edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Knabb, Ken. Situationist International Anthology. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981.

Nettlau, Max. A Short History of Anarchism. London: Freedom Press, 1996.

Could you recommend a book[s] which deal specifically with the Enrages and the commune, varlet, Roux, Hebert, the neighborhood assemblies etc.?

Kropotkin’s The Great French Revolution has some good stuff about the enragés and the neighbourhood assemblies. For more recent studies, see R.B. Rose, The Making of the Sans-culottes: Democratic Ideas and Institutions in Paris, 1789-1792 (1983: Manchester University Press), and Murray Bookchin, The Third Revolution: Popular Movements in the Revolutionary Era, Volume 1 (1996: Cassel).

Many thx.

And thx for the recommendation on Clark’s book. Just finished “Anarchist Moment.”